Brutal Truthtelling about Burnout

It’s getting popular to discuss burnout, which is great! It’s a conversation we need to have to counteract the self-promotional hustleporn that over-emphasize unhealthy work habits and suggests that success is contingent on sacrificing wellbeing. That ideology is the road to burnout. However, as our society has started to open up more about burnout, we've began to group so many aspects of workplace mental health under this single label that we've lost sight of the original sense of the word.

I don't want to trivialize the mental health struggled of anyone using the term burnout. Surely what they are experiencing is painful, and there is bravery in discussing such things openly. Additionally, there is a continuum along the road to burnout, and different interventions can help at different stages on this road. However, discussions of burnout really should be centered around honest truth-telling about the end stage that defines the term. At earlier stages of the road towards burnout, one might be able to drop a side project or take a mentalhealth day or a vacation and feel some relief. However, once in a condition of burnout, such things are insufficient. Discussing the journey towards burnout without its terrible destination may thus make burnout seem less dangerous than it actually is. Fighting a fire is different than rebuilding a burned-out building, but as Homer says, "When a fire starts to burn, there's a lesson to be learned."

The term burnout originally comes from the novel “A Burnt-Out Case,” in which Querry, a famous architect, is struck with a "terrible attack of indifference" that causes him to lose the ability to take pleasure in things that he previously enjoyed. The character travels to a Catholic Church run leper colony in the Congo, where Querry's emotional condition is likened to a "burnt-out case," a stage of the mutilation process caused by leprosy. Surrounded by people of faith, it is also compared to the Catholic idea of the “Dark Night of the Soul.” Thematically, burnout was thus treated as a particularly dangerous stage of an emotional disease, during which one became indifferent and suffers internal questions of belief, identity, and profession.

The idea of burnout passed from literary device to psychology via Dr. Freudenberger, a Holocaust survivor turned psychiatrist that opened a free mental health clinic for the hippies in the East Village of New York City during the 1960s. Many of the patients Dr. Freudenberger saw suffered from a bad combination of severe mental illness and unhealthy self-medication through drugs. Feeling that the social alienation of the flower children mirrored some aspects of the social alienation he felt as a young Jew during the Holocaust, Freudenberger’s volunteer work became obsessive and consumed more and more of his time until he suffered a strange prolonged bout of indifference and lethargy that required months to recover. This experience led Freudenberger to reflect on what had happened. He was surprised that his training as a psychiatrist didn't allow him to sense the warning signs of his own declining mental health. His reflection and follow-up clinical experiences led to a loose theoretical framework around burnout, which was popularized by his 1980 book "Burn-Out: The Cost of High Achievement."

Rather than leprosy, Freudenberger used an analogy for burnout that would be more familiar to his American audience, that of a burned-out building:

If you have ever seen a building that has been burned out, you know it's a devastating sight. What had once been a throbbing, vital structure is now deserted. Where there had once been activity, there are now only crumbling reminders of energy and life. Some bricks or concrete may be left; some outlines of windows. Indeed, the outer shell may seem almost intact. Only if you enter inside will you be struck by the full force of the desolation.

The two ideas of burnout as late stage emotional leprosy or the utter destruction of a burned-out shell of a building should give you an idea of its severity. It's what happens when some sort of process isn't properly managed, and self-destruction is nearly complete.

Several years ago, I experienced such a case of burnout. I entered the tech industry in 2010 after a medical discharge from the Army and a lengthy and difficult job search during the Great Recession. This sense of insecurity combined with my innate self-consciousness, ambition, and competitive streak to set me up for a long run of self-destructive behavior. I piled on responsibilities to demonstrate my worth and set my career on a positive track. I worked a full-time job requiring considerable travel, took 2/3 full time coursework in grad school, did considerable blogging, and did volunteer work, all at the same time. I had a 40 page career manifesto showing my life as a graph going up and to the right, accumulating accolades and promotions. I neglected sleep and self-care in the name of setting myself up for a stable future.

While I pushed myself hard, I had the hubris to think that I understood burnout and had sufficient self-awareness to notice my state and dial back my exertions as needed. Off and on, I experienced short bursts of exhaustion and depression, and I treated these symptoms with time off, extra workouts, or mental health days playing Sid Meier's Civilization.

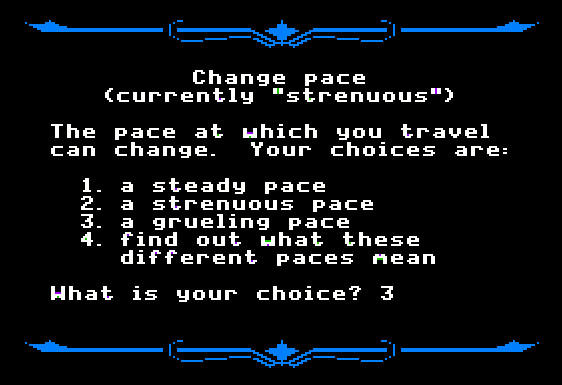

In retrospect, I was managing the symptoms, but I was blind to the fact that setting my life to the equivalent of "Grueling Pace" in the game Oregon Trail was increasingly taking a toll. I thus failed to deal with the underlying personality traits that were causing me damage. My ability to feel self-love only could occur when I achieved external accomplishment, and the threshold for such a feeling got higher and higher as I expected more from myself. Sure, I sporadically had "bad days," but I was being responsible and dealing with them. I still considered myself a professional "Rockstar" (cringe).

I felt like I had everything under control until one day, a burst of stress combined with years of slowly accumulated chronic exhaustion, transmuting me from superman to super broken man. It turned out, the symptoms of progression were not something I could detect in myself. I thought I had everything under control right until the end, when a switch flipped and everything changed.

My recovery took several months, but I've emerged a much different man. I ended up leaving my job, seeing a therapist, seeing a career coach, changing my career trajectory, and (at least attempting to) slow my pace of work. Once burned out, I don't think I could have recovered in any less disruptive manner. I was a burned-out shell of a building, and I had to rebuild myself, saving a single ember to ignite my passion for life.

All of this had a great cost. If I were to place myself on the chart in my career manifesto, I'd be well below the line. I'm not as great or accomplished of a man as I had envisioned, but I'm trying to be okay with that and instead focus on being a good man and living a "good life." I carry emotional scar tissue from the trauma my ego inflicted on my self, but at least I recognize that I am my own worst boss and critic, and now have some defense mechanisms around this.

So while people discuss burnout and potential cures, realize that many are talking about methods of prevention before burnout has occurred, not recovery after the fact. A small fraction of those folks discussing burnout may even be like me of several years ago, thinking that they are managing their symptoms, but not making the hard sacrifices needed to head off burnout altogether.

Here's my attempt at some burnout truth-telling. When you've hit burnout, you've failed to manage your ego and pushed yourself too hard. Two weeks of vacation will be insufficient to recover. There is likely a relationship between how long you pushed yourself hard, and your recovery time, but it's fair to say that you will feel numb to life and be semi catatonic for 3+ months. Our society does not provide many safety mechanisms for such a thing, so probably, you’ll lose your job or quit. However, if your employer is understandable, you might be able to take some unpaid leave.

As painful as burnout is to you, it's doubly so for your friends and loved ones. They likely have been telling you that you've been pushing too hard, but you ignored their warnings. Once burned out, you will be difficult to be around and occasionally be emotionally abusive to your friends and loved ones. Many people you thought were your friends will disappear. You may also damage close friendships beyond repair.

It takes years of bad decisions, constant hustle and poor self-awareness to get to burnout, but once you’re there, you can’t escape. You are a spiritual casualty in the war of ambition, and recovery takes months and the sacrifice of sacred cows. You will likely have to kill a part of your ego and adjust expectations for your life. You might end up a different person on the other side.

At least, I did.