System/360 at 50

On April 7, 1964, Tom Watson Jr. stood at the front of a conference room in IBM's Poughkeepsie, NY research lab. Looking beyond the podium and out into the audience, Watson saw two hundred influential writers and editors belonging to the 1960s tech cognoscenti. Looking a little closer, he saw a series of television cameras, broadcasting and recording the announcement across time and space. Standing in front of this audience, Watson palpably sensed that many of the reporters were skeptical of IBM. Then again, Watson had learned to win over skeptics when flying Lend Lease missions to the Soviet Union during World War II. If he could win over skeptical Soviets, surely he must be able to reach these men.

Although Big Blue had successfully entered the digital computer market with the IBM 701 in 1953, by the early 1960s, IBM's computer portfolio seemed a jumbled mess. The differing needs of research labs, corporations, and medium-sized businesses led IBM to develop and market products with mutually-incompatible architectures. This led to destructive competition between engineering teams for funding, and the experience of IBM salesmen having to "sell against themselves" when teams of IBMers disagreed as to which IBM product best fit a particular client. While IBM found itself occupied with internal strife, smaller and more nimble competitors chipped away at IBM's market share by focusing on particular segments of the computer market. Given that Watson was instrumental in pushing IBM towards electronics, this hurt him personally. Indeed, less than one year earlier, Seymour Cray and the Control Data Corporation released the CDC 6600, which was world's fastest computer, leading Watson to pen a letter criticizing IBM for letting “our industry leadership” fall to a CDC lab of “34 people, including the janitor." Meanwhile, IBM's successful high-end and mid-range data processing systems faced erosion of profits due to competitors releasing systems with superior price/performance. Most painfully, one of these competitors was General Electric, hitherto the largest customer of IBM mainframes, which had recently released the GE 400 and the GE 600 lines. Threatened by internal divisions and nimble competitors, IBM seemed to be in significant decline, and Watson felt it.

Tom Watson knew that, to be successful, IBM would have to convince these skeptical spectators that it could restlessly reinvent itself. It needed to end the narrative of IBM as a declining dinosaur from the era of punched cards and Hollerith tabulating machines by demonstrating that IBM could engineer new and innovative products.

Given the uncertainty over the strategic direction that IBM would pursue, it was symbolic that Watson stood overshadowed and framed by a large sixteen point mariner's windrose. As a longtime sailor, Watson knew that windroses such as these were used by ancient mariners dating back to the dawn of civilization. In Greco-Roman antiquity, the primary points of the windrose denoted the four wind gods named Boreas, Eurus, Notos, and Zephyrus, who sent Odysseus on an unplanned ten year adventure on his return voyage to Ithaca following the Trojan War. Thinking back on IBM's own decade-long odyssey with electronic computers, Watson contemplated how these winds were also the figurative forces that scattered IBM's product offerings in incompatible directions.

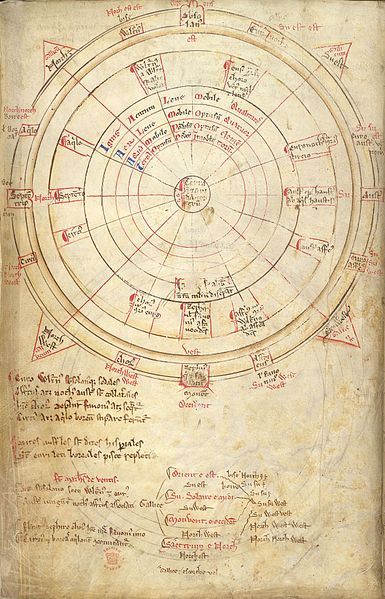

Unlike the four or twelve winds of the classical work, Watson's System/360 windrose more closely resembled this diagram from the thirteenth century classic Liber Additamentorum.

Watson clearly believed that IBM could again master the winds and chart a new course in the competitive landscape of the 1960s. Just as he sailed his ship the Palawan further up the northern coast of Greenland than any other civilian vessel, winning the New York Yacht Club's highest award and the Cruising Club of America's Blue Water Medal, he would pilot Big Blue further than anyone had hitherto thought possible. Similarly, he would push IBM innovation to the level that it would impact the arc of history to the same degree as when Captain Cook explored the Pacific.

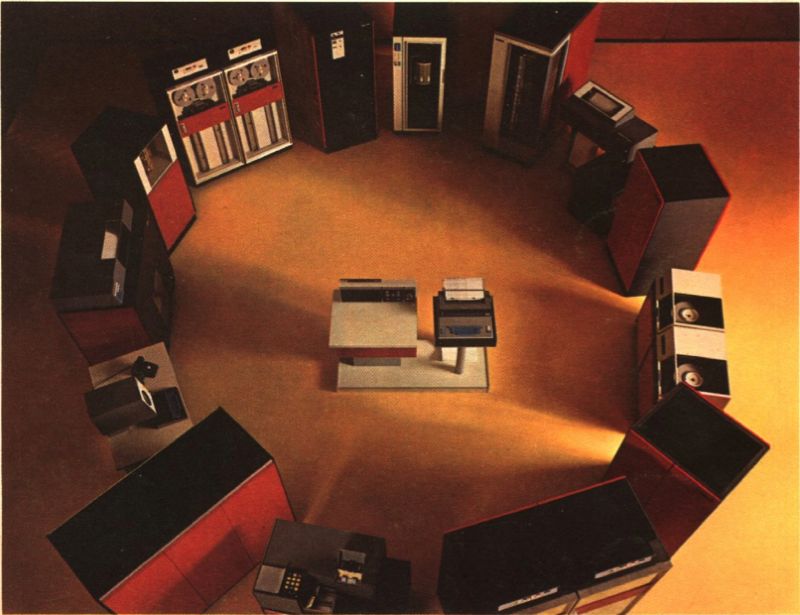

Standing in front of this skeptical audience and framed by the four wind gods of antiquity, Watson announced IBM's long-awaited New Product Line (NPL). This line embraced several distinct models across a broad range of price and performance. Most importantly, these systems shared a single compatible architecture, making it suitable for the data processing and scientific workloads of organizations of all sizes. In recognition of this unifying architecture, IBM's New Product Line was called IBM System/360, signifying that this system would handle the full compass rose, including all 360 degrees of computing.

Stepping down from the podium, Watson watched Bob Evans and Dr. Frederick Brooks, the masterminds of the System/360 project, answer technical questions and provide a live demonstration of the System/360 Model 60. Watching the audience during the demo, Watson sensed that the skepticism had melted away, and he felt that that Big Blue had corrected course and would steer the direction of computing for decades to come. He envisioned IBMers in dark blue suits, white shirts, and honest ties meeting customers over lunch and golf. He envisioned firm handshakes and closed sales and deepening collaboration between IBM and organizations of all sizes and types for decades to come.

The System/360 is ready to run your workloads, Mister Customer. Contact your IBM representative for more information.

Final Thoughts

From a technical standpoint, the IBM System/360 was an unparalleled breakthrough. Due to its unified architecture, the System/360 was the first family of computers to emphasize the primacy of software. By establishing a common architecture across products and guaranteeing backward compatibility in future generations, it became feasible to develop software products for the long-term. This allowed the development of significantly more complex operating systems, middleware, and applications. In modern terms, the System/360 created the first App Ecosystem. Similarly, the System/360 created a "modular design" that provided standardized interfaces for peripheral devices, leading to a large market for third-party System/360 "plug-compatible" components, such as tape drives, hard disk drives, and printers. This eventually led competitors to market peripherals for the System/360.

From a business standpoint, the System/360 restored faith in IBM's engineering prowess. While CDC, RCA, GE, and others would continue to market their computers, IBM's System/360 became the de facto standard for computing. In the first month of availability, IBM sold over 1,100 System/360 computers, an unprecedented amount for that time. By the end of September, IBM had sold over double that quantity, equaling one fifth of all computers sold by IBM since 1953. By 1970, IBM's total revenue more than doubled to $7.5 billion dollars and the number of installed IBM computers tripled to 35,000.

Due to these reasons, the IBM System/360 is considered by many to represent the dawn of modern computing. Countless customers have made the System/360 architecture the foundation of their business, establishing a long term partnership with IBM that has endured for over fifty years. The modern zEC12 and zBC12 systems continue the legacy of the System/360 and enable customers to continue to leverage their past mainframe investments alongside new Linux workloads and cutting-edge peripherals, such as the IBM DB2 Analytics Accelerator (IDAA).

The IBM mainframe has evolved continuously since my grandfather worked with the System/360 in the late 1960s, and numerous Millennial Mainframers such as myself and the many students involved in the Master the Mainframe World Championship continue to make the IBM mainframe the cornerstone their careers. If you are interested in celebrating the legacy of the System/360 and the bright future for contemporary IBM mainframes, join IBM's Mainframe50 global broadcast event tomorrow April 8th from 2-4:30pm Eastern Standard Time. Please register at http://www.livestream.com/ibmsystemz. Additionally, check out IBM mainframe history, engines of progress, and Generation z initiatives at http://www.ibm.com/mainframe50/

Here's to the next 50!!!

This post was originally hosted on the Millennial Mainframer blog