zEnterprise - Mainframe Hybrid Computing

Despite derision as a dinosaur doomed to gradual extinction, a recent breakthrough in mainframe technology has the potential to transform the world of modern data centers. On July 22, 2010, IBM released the zEnterprise, a product that combines mainframe and distributed computing environments into what Rod Atkins, IBM’s head of hardware, called “the industry’s first multi-architecture platform” (Greenberg, 2010). Under such a platform, the mainframe is transformed from a command-and-control system used for batch processing, transaction management, and virtualization into a brain-like system of systems that manages disparate workloads across System z, x86, and power systems running z/OS, Unix, Linux, and Windows (Bartlett, 2011). Between the IBM marketing materials and the subsequent IT press coverage, the zEnterprise has been lavished with characterizations of mythological proportions, including that it is a “data center in a box” (Morgan, 2010) and a Tolkienesque “one node to control them all” (Saran, 2011). IBM engineers apparently thought along similar mythological lines, as they gave zEnterprise development the codename Project Griffon in honor of the ancient creature possessing the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle (Doyle, 2010).

This blog uses three methodological lenses to break through IBM myth and marketecture in order to realistically examine and appraise the impact of zEnterprise on the design and management of data centers.

- Through the use of a historical lens, we will contextualize IBM’s design of the zEnterprise within the narrative of data center evolution through the mainframe era, the PC era, and the current so-called post-PC era characterized by smartphones, tablets, and internet appliances ubiquitously connected to cloud-based services.

- Through the use of a technical lens, we will analyze the components underlying the zEnterprise stack.

- Through the use of a business lens, we will examine a fictional zEnterprise deployment to identify the potential business value and inhibitors that will affect future adoption and deployment.

In addition to demonstrating that the zEnterprise hybrid-architecture is a technological breakthrough that could lead to a paradigm shift in computing, this blog argues that:

- The zEnterprise brings into question the assumption that a single architecture or platform will dominate data centers. Just as Stewart Alsop predicted the death of the mainframe by 1996, technologists such as Steve Jobs have argued that we live in a “post-PC” centered on cloud computing and portable devices (Hiner, 2010). In reality, data centers will continue to use a variety of architectures optimized for different workloads, suggesting that unified multi-architectures such as zEnterprise will provide substantial business value.

- By becoming a system of systems, the zEnterprise extends traditional mainframe-style workload management according to complex business rules across heterogeneous local- and cloud-based platforms. This will improve hardware utilization rates and reduce the sprawl of servers and networking equipment, resulting in more efficient and environmentally-friendly data centers with decreased personnel requirements (Ebbers, 2011, 34).

- The implementation of zEnterprise will face political and social resistance from by the mainframe and distributed communities. Mainframe professionals may perceive integration with PCs as potential causes of mainframe downtime. PC professionals may oppose zEnterprise due to preconceptions about mainframes being antiquated, inflexible, and overly expensive. Additionally, the unification of the distributed and mainframe communities will be a political challenge due to the historical and cultural differences between these communities. The first hybrid data centers will thus be built in locations with low levels of architecture bias, such as new “green field” projects in India and China (Kernochan, 2011).

History of the Data Center

During the early 20th century, governments and companies began to view technology as the key to understanding complex systems. Technological successes, such as the novel machines used by Herman Hollerith to tabulate the 1890 U.S. Census in one eighth the expected time, demonstrated that technology was key to gaining timely and actionable information (Maney, Hamm, & O’Brien, 2010, 24). Once IBM, Remington Rand, and other young technology start-ups began to commercialize and sell these technologies, organizations formed the first government, scientific, and enterprise data centers based around the use of mechanical tabulating machines and 80 column punch cards. The architecture of these first data centers was quite simplistic, often consisting of a room with tabulating machines and repair equipment and a separate facility for punch-card storage. Indeed, one of the largest IT problems of this period revolved around how to effectively store and organize punch cards. Because each IBM punch card held no more than 960 bits of data, it did not take long before pallets of punch cards filled entire rooms, buildings and warehouses.

Following Claude Shannon’s 1937 thesis on using electrical relays to solve Boolean logic, the birth of electronic computers ushered in the mainframe era and led to several significant changes in the architecture and popularity of data centers. First, data center managers solved the headache of punch card storage by transferring data onto magnetic media, reducing physical footprint through the first data center consolidation (Maney, 2010, 42). Second, the ability of the IBM System 360 and other mainframes to execute software led to a dramatic expansion in data processing workloads (Neubarth, 2008). Standardized software languages, such as COBOL and FORTRAN, allowed the construction of the earliest “killer apps,” customized applications capable of complex analysis and the automation of mundane and repetitive tasks. Third, the increased complexity of electronic computers affected the skill sets possessed by data center professionals. While the staff of mechanical tabulating machines could work interchangeably in different roles, technological complexity forced mainframe professionals to specialize in software, storage, cabling, and other areas.

The key legacy of the mainframe era was the formation of a centralized command-and-control model of computing. Due to their high cost, early business machines were highly regulated and controlled resources that were time-shared between various departments or businesses. As a result, one major responsibility of the data center was to balance competing computing demands from different clients. In order to ensure equitable distribution of resources, client organizations would have to submit batch jobs that would be spooled and executed according to complex business rules (Stephens, 2008, 50). With so many important business functions depended on the centralized processing of data, companies managed their mainframe data centers like a battleship, assigning their data center professionals highly circumscribed responsibilities under a centralized control structure governed by strict rules and regulations (Stephens, 2008, 135-148). Although advances in mainframe technology provided dramatic increases in processing capacity and new functionality such as timesharing between several thin-client “dummy” terminals, this centralized model remained dominant in data centers into the early 1980s.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, miniaturization and drops in the cost of electronic components led to the development of the personal computer (PC) by Xerox, Apple, IBM, Tandy, Commodore, and other various companies. For mass society, this new device transformed information technology from an abstract concept into an indispensable personal tool, leading to Time Magazine’s decision to name the PC the 1982 Person of the Year (Friedrich, 1982). For the corporate world, the PC represented a paradigm shift in the way that many organizations viewed their computing resources and architected their data centers. By enabling organizations to equip individuals with their own personal computer, the so-called PC Revolution substantially democratized all aspects of computing. Rather than depending on a “priesthood” of IT professionals to provision centralized resource or execute batch jobs (Doctorow, 2009), end users with a PC could now locally execute data processing workloads and “serve” applications and data to other “client” PCs over a shared network using the TCP/IP client-server model (Clark, 1988). Because the PC model appeared to offer the benefits of computing without having to invest in costly centralized data centers, technology pundits, such as Stewart Alsop, began to predict that the last mainframe would be unplugged on March 15, 1996 (Spruth, 2010, 6). While predictions of the mainframe’s demise ultimately proved unfounded due the PC’s architectural unsuitability for large-scale batch processing and transaction management workloads, the mass individual adoption of PCs within organizations of all sizes established distributed computing as the dominant model for most workloads, leading PC-based servers to be characterized as Industry Standard Servers (Pontiatowski, 2009, 13).

As the Internet grew into a mass central hub for research, commerce, and social interaction, numerous organizations struggled to serve their PC-based resources to increasing numbers of clients while maintaining an acceptable level of performance. Though able to effectively share files and printers with a few users across a workgroup, the egalitarian design philosophy of distributed computing made it difficult for the PC architecture to scale (Neubarth, 2008). In order to meet the needs of growing networks and internetworks, computer manufacturers had to engineer purpose-built PCs capable of serving centralized resources to ever greater numbers of client workstations. Because these servers were more critical than the typical workstation, companies typically secured these computers in so-called data closets or computers rooms, forming the first data centers oriented around the PC architecture. Despite constant improvements in server technology in line with Moore’s Law, these early PC-based data centers eventually began to suffer from skyrocketing operational costs and downtime due to the disorderly, messy, and uncontrolled accumulation of server and networking equipment. To some data center managers, the PC-based servers appeared to be like rabbits that multiplied daily (Poniantowski, 2009, 3) or “a voracious beast, eating space, breathing in cold air, breathing out a never-ending flow of hot air, and consuming power in ever increasing amounts” (TechRepublic, 2011, 3). To counter this server sprawl and bring IT under control, organizations began to heavily invest in ways to cut costs and rationalize their IT infrastructure. On the technological side, companies invested in a myriad of new products to simplify their IT infrastructure, including standardized rack sizes, elevated floors, cable trays, server clustering, blade architecture, and virtualization. On the personnel side, companies recruited technical mangers to establish order in the data center and keep operations within schedule and budget, resulting in the professionalization of data center management and the examination and codification of best practices in standards documents such as TIA-942 (TIA, 2005). Through these investments, companies were able to develop the open PC architecture and transform their early computer rooms into the modern scalable data centers of the Internet Age.

The recent proliferation of internet-based applications and services has led numerous technology pundits to characterize cloud computing as a technological paradigm shift as disruptive the invention of the PC. While cloud computing will certainly be a dominant and disruptive force in IT in the coming years, this technology is less a technological revolution than the result of a gradual decades-long convergence between mainframe and PC technologies. Due to the growth of the Internet, the architecture of PC-based server and data centers has assumed ever increasing levels of centralization. As the PC server has become more centralized, it has architecturally implemented proven mainframe technologies, such as virtualization and server clustering. As the PC-centric data center has become more centralization, it has adopted the sorts of circumscribed responsibilities, centralized control structures, and strict rules and regulations that characterized the management of mainframe data centers in the past. In this light, the shift in client-server computing towards mainframe-like levels of centralization has reached its zenith in modern Generation IV data center; where the concentration of large-scale x86 computer clusters in shipping containers attempts to transform the PC architecture into a platform capable of the massive parallel execution of general workloads. In contrast to the PC’s move towards centralization, the mainframe has moved towards greater flexibility and openness through the implemented of PC-centric standards and technologies, such as TCP/IP, Unix, Java, and Linux (Neubarth, 2008). These efforts sought to combat predictions of the mainframe’s demise by reducing costs and keep the mainframe relevant in the Internet Age. As shown by the convergence between the PC and mainframe architectures, modern data centers have simultaneously experienced cost pressure to pursue economies of scale by moving towards mainframe-like levels of centralization and user pressure to implement a model of computing that allows for PC-like flexibility and abolishes centralized control in favor of self-provisioning. In other words, cloud computing is the direct result of the convergence between the mainframe and distributed computing architectures.

Technical Anatomy of the zEnterprise Hybrid Architecture

System z Mainframe

Despite predictions by Stewart Alsop that the last mainframe would be unplugged on March 15, 1996 (Spruth, 2010, 6), the modern mainframe remains critical to many enterprise-class data centers, including those of the top 59 global banks, 23 of the top 25 US retailers, and 9 of the top 10 global health insurance companies (Kooijmans, 2010, 17). When asked in 2002 why the mainframe did not die, Alsop admitted that “it’s clear that corporate customers still like to have centrally controlled, very predictable, reliable computing systems – exactly the kind… that IBM specializes in” (Neubarth, 2009). In other words, it was wrong to equate the explosive growth of PCs in the 1990s with the decline of the mainframe as these architectures represent substantially different styles of computing. While the PC democratized and popularized computing, the mainframe has remained dominant in the areas of large-scale batch processing, transaction management, and virtualization due to its ability to its high utilization rates and strength in massively parallel applications. Judging by the fact that the MIPS running on the mainframe grew by 35% in 2010 (Hingley, 2011) and 57% of respondents in a recent BMC survey planned to move new workloads to the mainframe in 2011 (BMC Software, 2010, 4), System z remains a healthy platform with a specialized niche in Fortune 500 data centers.

The two models of the latest generation of System Z mainframes reflect IBM’s objective to maintain its strong relationships with Fortune 500 customers while expanding mainframe technology into non-traditional data centers through reduced pricing. For Fortune 500 customers interested in cutting-edge technology, the enterprise-class z196 offers a 60% boost in system capacity and a 100% boost in memory over the previous z10 (Friedman, 2011, 39), as well as the world’s fastest processor, which is capable of the out-of-order execution (OOO) of instructions across up to 80 5.2GHz cores (Morgan, 2010). These upgrades allow the z196 to execute even high levels of parallel operations, including large-scale transaction management and the simultaneous virtualization of thousands of Linux servers. For smaller sized organizations, the $75,000 business-class z114 is the least expensive mainframe ever, effectively competing against specialized UNIX servers from Dell, HP, and Oracle (Clabby, 2011). Despite this lower price point, the z114 offer an 18% per core performance improvement over its predecessor and a far higher degree of performance granularity, allowing for customers to right-size their mainframe to execute between 26 and 3,100 MIPS (Lotko, 2011). Numerous efforts, including a 5 – 18% reduction in monthly licensing charges (MLC) and deeply-discounted hardware, software, middleware, and maintenance bundles for first-time mainframe customers, demonstrate that IBM is aggressively seeking to push System Z into non-traditional data centers in order to establish zEnterprise as the platform of choice for data center consolidation, data analytics, and private clouds. (Radding, 2011).

System Z Blade Center Extension

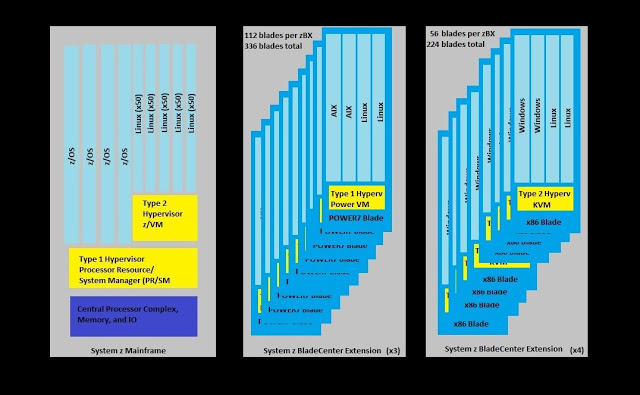

The System Z Blade Center Extension (zBX) is the physical means to connect up to 192 IBM blade servers to a z114 or z196 mainframe to form a unified node called an ensemble (White, 2011, zEnterprise 196, 1). Although resembling a typical IBM BladeCenter, the zBX does not contain the traditional controller hardware to independently manage blades, as the System z Hardware Management Console (HMC) executes all provisioning and workload management functions for its associated ensemble over a 10 Gigabit multimode fiber-optic Intra-Node Management Network (INMN). This is completely separate from the 10 Gigabit multimode fiber-optic Intra-Ensemble Data Network (IEDN) that carries data within an ensemble (White, 2011, zEnterprise URM, 296). Each zBX can hold a variety of different IBM blade servers, including POWER7 blades, x86 blades, and specialized and purpose-built optimizers designed for data analytics. This platform heterogeneity enables an ensemble to run numerous hypervisors (PR/SM and z/VM on the mainframe, PowerVM on POWER7, and KVM on x86 blades), enabling a single ensemble to run all major mainframe and distributed operating environments, including proprietary products from IBM, open-source Linux offerings from Red Hat and SUSE, and proprietary Windows offerings from Microsoft (Radding, 2011). Because of its close association with System z, the zBX contains more redundant components than a typical BladeCenter in order to achieve mainframe-like levels of reliability, accessibility, and serviceability.

Unified Resource Manager

The Unified Resource Manager (zManager) is software tool that extends the mainframe’s strengths in automation and policy-based management across a zEnterprise ensemble composed of heterogeneous blade servers running all major mainframe and distributed operating environments. By integrating with z/VM, PowerVM, and KVM-based hypervisors at the system firmware level, the System z mainframe perceives all blade resources in the ensemble as internal components of the mainframe environment, transforming the zManager into a single control interface capable of controlling and automating the provisioning and management of virtual machines throughout the ensemble (Kajeepta, 2011). This offers data center managers to ability to set uniform service level agreements (SLAs) in terms of performance, business importance, and other discretionary goals that the zManager can use to determine how, when, and where specific workloads should be executed (Spruth, 2010, 49). Once these goals are set, the zManager has powerful reporting capabilities that can show managers where specific workloads are running in an ensemble, how these workloads are executing compared to SLAs, where potential bottlenecks may be reducing performance, and actions that the zManager has automatically taken to ensure that SLAs are met (White, 2011, zEnterprise URM, 296). Additionally, the zManager’s free and open API (available in late 2011) allows IBM and independent software developers to develop middleware data center applications to harness and extend the tools of the zManager (Hares, 2011).

Fictional Business Case for a zEnterprise Data Center

In January 2011, the McBride Insurance Company (MIC) completed their acquisition of the Riegger Insurance Society (RIS). As a 50 year old insurance company, MIC possessed a loyal client base and strengths in the sale of traditional insurance products in person and on the phone. MIC acquired RIS in order to gain a lucrative online-only business unit specialized in selling state minimum auto coverage through well-designed Web 2.0, Android, and iOS interfaces. Shortly after the official announcement of the acquisition, the CIO ordered the data center manager to reduce operational IT costs by unifying and consolidating both data centers down to a single 40ft x 48ft data center located in the Wacker Drive high-rise office in downtown Chicago, Illinois. Soon after studying the IT inventory of RIS, the MIC data center manager realized that this data center consolidation would face significant problems surrounding server sprawl and multi-architecture complexity. As an older company, MIC’s data center runs numerous critical workloads on legacy mainframe platforms, including COBOL applications running under the Customer Information Control System (CICS) transaction manager tied to DB2 databases. Additionally, the MIC data center runs its web and data analytics applications on the AIX environment running on the POWER7 platform. In contrast, the RIS data center ran a mix of Red Hat Linux and Windows Server 2008 workloads on HP servers, including numerous critical business applications tied to the Microsoft .NET and Azure platforms. After learning about zEnterprise during a SHARE conference, the MIC data center manager and CIO decided to consolidate onto this cutting-edge platform in order to reduce the complexity caused by acquisition of RIS, automate the consolidated data center to minimize operation cost increases, and move towards an agile hybrid cloud infrastructure.

Design of a zEnterprise Data Center

The MIC data center is composed of two identical ensembles, which are each composed of one z196 and seven zBXs (3 filled with POWER7 blades running AIX and Linux and 4 filled with x86 blades running Windows and Linux). At the physical level, each ensemble is composed of one mainframe and 560 blades. At the logical level, each ensemble is running four copies of z/OS, 1370 copies of Linux, 672 copies of AIX, and 448 copies of Windows. This means that the MIC data center totals two mainframe and 1120 blades running eight copies of z/OS, 2740 copies of Linux, 1344 copies of AIX, and 896 copies of Windows.

Logical Architecture of each Ensemble

Physical Architecture of the Data Center

Note: In order to focus on the components of the zEnterprise, this design abstracts away numerous data center components, including disk storage, tape backup, power distribution units, back-up generators, and any additional peripherals such as enterprise printers.

The physical architecture of the MIC data center is designed according to the standards established by the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Handbook and supplemental information provided in IBM’s zEnterprise 196: Installation Manual for Physical Planning and zEnterprise BladeCenter Extension: Installation Manual for Physical Planning. The MIC data center is located in a small room located in a skyscraper along Wacker Drive in downtown Chicago, Illinois. This room is 40 ft wide and 48 ft long with a 24 inch raised floor utilizing standard 24 inch floor panels. The two ensembles are organized into two rows each for a total of four rows. Because this data center is using air-cooled mainframes, the z196 units are places at opposite ends of the data center to disperse their heat signature. The Computer Room Air Conditioners (CRACs) are located at the end of the hot aisles opposite from the mainframes because the z196 units extend into the hot aisle.

I/O Cabling

All network connections in the MIC data center run over 10 Gigabit multimode fiber optic cables. Each node in an ensemble is directly connected to its z196 over separate data and control networks, and the two z196 units are connected to each other, each DS8000 storage unit, and any external resources. All units in this data center use top exit I/O cabling run in cable trays above the rows of equipment.

Power

| Unit | Power Usage (kW) | # Units | Total Usage |

| z196 | 24.3 |

2 |

48.6 |

| POWER zBX | 79.3 |

8 |

634.4 |

x86 zBX |

40.9 |

6 |

245.4 |

928.4 |

All components in the MIC data center run on standard 200V to 240V, 50/60Hz, single-phase power. Each mainframe requires 8 power receptacles and each BladeCenter required a single power receptacle, meaning that the computing equipment requires a total of 104 power receptacles. All power cabling is run under the subfloor plenum due to requirements dictated by IBM. The total power usage of computing equipment in this data center is 928.4 kW.

Cooling

|

ASHRAE Declarations (English) for Example Data Center

|

|||||

|

|

Heat Release

|

Airflow Nominal

|

Airflow Max

|

Weight

|

Dimensions

|

|

|

kBTU

|

cfm

|

cfm

|

lbs

|

W x D x H

|

|

z196

|

92.8

|

2700

|

3500

|

4799

|

67.6 x 71 x 79.3

|

|

zBX – POWER

|

157.4

|

4224

|

6560

|

5440

|

102.0 x 43.3 x 79.8

|

|

zBX – x86

|

78.7

|

2112

|

3280

|

2720

|

51.0 x 43.3 x 79.8

|

This MIC data center is cooled by two down-flow CRACs located at opposite ends of the room. Because the total heat release of this data center is 328,900 BTU, the combined capacity of these CRACs must exceed 27.4 tons

Added Value of zEnterprise

By consolidating their heterogeneous IT landscape onto the zEnterprise, MIC achieved significant added value in three key areas. First, the zEnterprise multi-architecture platform allowed them to simply their server and network infrastructure by shifting their z/OS, AIX, Linux, and Windows workloads to a unified and consolidated system. This allowed the data center to expand their IT capacity and capabilities while maintaining their current physical footprint and reducing their number of network devices. Second, the zEnterprise’s high degree of automation reduced the number of required data center professionals, allowing MIC to reassign or terminate employees to reduce operational cost. Third, the zEnterprise dramatically cut the cost of moving to a hybrid cloud architecture by concentrating the provisioning and management of all systems in two z196 mainframes. With additional middleware products from IBM, BMC, or CA, data center professionals could manage their IT infrastructure under a hybrid-cloud model, enabling the auto-provisioning and management of virtual servers locally in the data center and on the IBM and Amazon public clouds through a single unified web interface (Buzetti, 2011, 1). The most significant gap in MIC’s data center infrastructure is their inability to use the zManager or middleware products to monitor and manage the Windows Azure cloud resources used by their .NET applications. Nevertheless, the open zManager API enables such capacities to be added in the future.

Although the business value of this specific case will differ from other data centers depending on whether they are adding a mainframe, a zBX, or both, all data center implementations would gain value in the areas of simplification, automation, and the cloud. For Fortune 500 data centers with mainframes, the primary added value of zEnterprise is the zBX and the zManager, which extends many of the mainframe’s benefits to their distributed environments. Many of these data centers have some degree of unified management through IBM Tivoli middleware products, but the integration under the zManager makes this far more seamless and potentially eliminates the need for some middleware products. For data centers without mainframes, the primary value added is the mainframe, which offers the chance to massively consolidate distributed workloads onto Linux on System z or deploy a cloud-in-a-box.

Inhibitors to zEnterprise Adoption

The greatest obstacle to zEnterprise adoption will be the proverbial 8th and 9th layers of the OSI model: people and politics. Since the PC Revolution, the data center world has been split between professionals that work with mainframes and professionals that work with distributed systems. This split is often replicated in organizations in the form of distinct departments that report directly to the CIO. For better or worse, these communities often do not communicate with one another and occasionally fight over how or where specific workloads or applications should run. Because many of these data center professionals are unaware of the convergence of mainframe and distributed technologies, personnel from both communities will likely view the zEnterprise hybrid architecture with distrust. The strongest resistance will likely come from the distributed community, as deployment of the zEnterprise means that the provisioning and management of distributed computers will become more automated and move to the mainframe. This could potentially signify a political shift in favor of mainframe professionals and layoffs for distributed professionals. Because of the strong architecture bias of these two communities, the first true deployments of the zEnterprise will likely occur in “green field” projects in developing countries (Clark, 2011). Similar to W. Edwar Deming’s work of continuous management in Japan, this technology will likely have to prove itself in emerging economies before winning acceptance in the developed world.

Conclusion

When viewed from the historical development of the modern data center, IBM’s decision to integrate PC and mainframe technologies into a hybrid multi-architecture platform appears a very prescient move. The PC and mainframe architectures have been converging for years, ultimately intersecting in the cloud computing model of centralization, self-provisioning, and personalization. Although the commodity pricing and openness of the PC architecture has enabled it to become the dominant technology in many modern data centers, the mainframe still possesses numerous advantages in the areas of automation, efficiency, security, reliability, accessibility, and scalability. By combining these traditional advantages with the mainframe’s new role as a system of systems capable of automatically managing workloads across x86, power, and cloud architectures, IBM has arguably created the ideal foundation for hybrid clouds. Given the heterogeneous IT infrastructure of many enterprise data centers, the zEnterprise offers a means to counter platform divergence and server sprawl through automation and simplification. By providing a single interface to control and automate workloads across platforms and hypervisors, the Unified Resource Manager (zManager) allows data center personnel to architect and automate a highly optimized environment where each workload is matched to its ideal platform. Just as Toyota engineered the Prius to intelligently distribute powertrain requirements between an electric motor and an internal-combustion engine, IBM engineered the zEnterprise to intelligently distribute IT workloads between mainframe logical partitions (LPARs) and blade computers running Intel and power processors. The zEnterprise thus forgoes a one-size-fits-all approach in order to provide a best-fit solution for the execution of each workload, potentially increasing data center efficiency, flexibility, and simplicity.

This post was originally hosted on the Millennial Mainframer blog